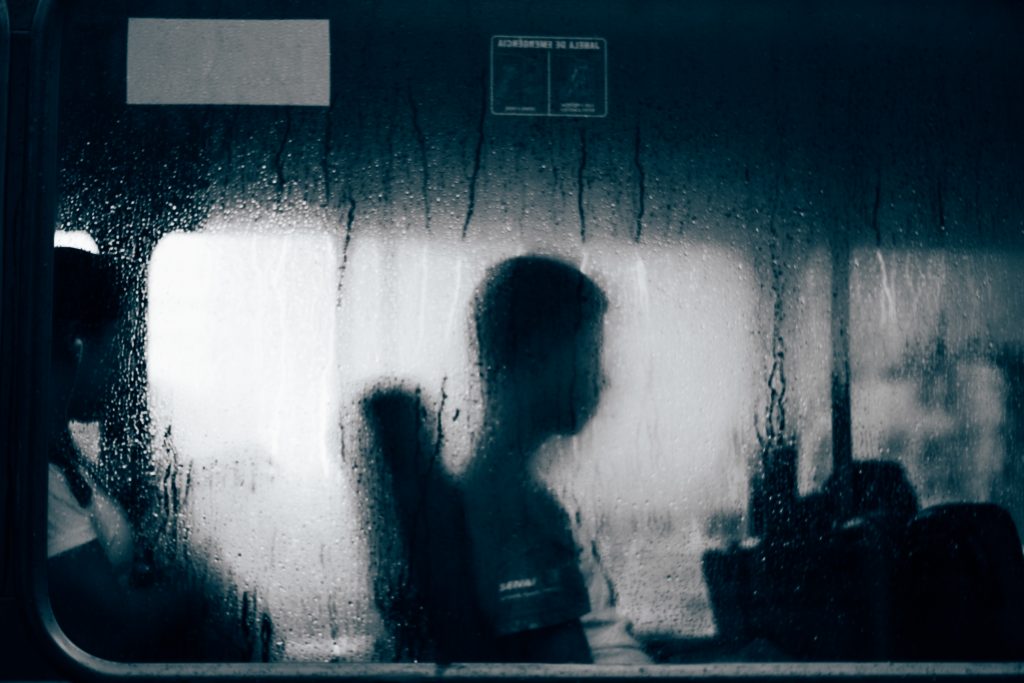

When you drive people from here to there, and when they sit in your back seat, it’s easy for them to forget you’re there. I suppose it makes sense, since a lot of people never even make eye contact with me. They get in the back and I half turn and say hello and their voice hits me in the side of the head and I turn and look at my phone to see where they want to go. So, I’m just half-a-head to them, at best, or an ear, and they’re a voice, at best, or the moving blur of a being, and we go from there, various pieces of various humans hurtling through the air.

But a strange thing happens: when you drive people from here to there, and they forget you’re doing the driving, you’ll hear all sorts of things. Mostly things that will break your heart. You’ll hear wives talk to representatives at domestic abuse shelters, trying to make arrangements for a night or two, that’s all, just a night or two. You’ll hear these same women talk to CYS and wonder why they can’t get their kids back from the kids’ dad, and they’ll talk about how they lost their car, or how they had to pick up their child early from school because they didn’t know if Dad was going to show up and then she’d never see her again, and that little child will be right there in the back seat, and you’ll wonder how it feels to be seven, in a strange car, while Mama goes on and on, explaining why your old man is a piece of shit.

Those are their words, not yours.

When you drive people from here to there, you’ll catch a glimpse of their eyes in the rearview, eyes staring out the window at nothing in particular, or maybe at the sun breaking through a late January day, or maybe at the traffic going in the other direction, always going, car after car after car, and you’ll wonder if that’s where she wants to be headed. Anywhere but where you’re taking her.

And then, when you’re finished driving these people from here to there, after you pull into the decrepit parking lot of an old apartment complex, and you make your winding way through the brick buildings, and you pull up to stop, she’ll shield the phone from her voice and she’ll say thank you. And there will be something about the way she says thank you that makes you realize she knew you were there, she knew, and she didn’t want you to hear it all, but she also didn’t mind you heard because no one listens anymore and she is thankful you were okay listening to all of it, even indirectly, even if it was only aimed at the back of your head, or one of your ears.

You’ll realize people are more than the pieces you can see, more than faces or eyes or slumped shoulders. They are made up of good days and really, really bad days and months and years and a thousand miles. They’re phone calls and disappointments and, even then, they’re sometimes still hope, too. Hope that’s been shattered and then swept up into a pile and gathered together and, for some unknown reason, kept from the dustbin. People are all kinds of crazy things, and the craziest of these is hope.