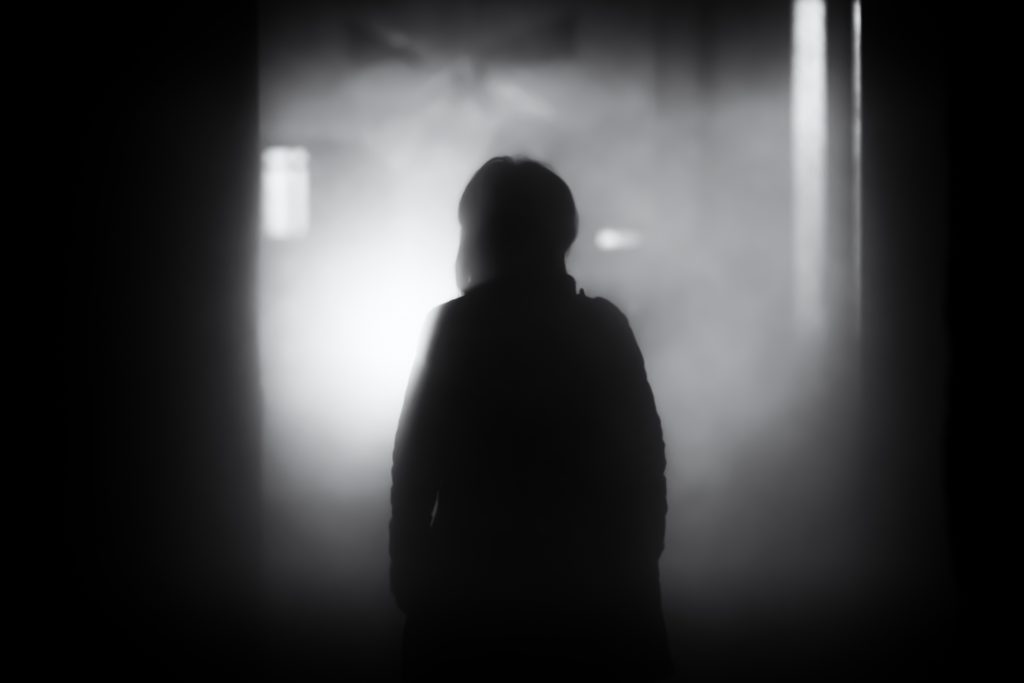

It would have been the perfect horror movie scene if she would have been holding an axe. As it was, she stood there in the cold, her silhouette framed by the garage door light. I pulled the car further in the driveway, towards her, and she limped out into the darkness. This was definitely not the George my app said I’d be picking up.

“Are you Uber?” she asked in a crackly voice.

“Yeah,” I said, smiling. “Are you George?”

“George is my son,” she said, and she didn’t sound amused by my lighthearted question. “He said this would be easy. Can you wait fifteen minutes?”

Fifteen minutes? That seemed a little excessive.

“Ma’am,” I said, trying to be polite. “I can head out and you can call another driver when you’re ready. They’ll be here when you need them.”

She wasn’t happy.

“How about five minutes?” she said.

“Okay,” I agreed, reluctantly.

She reappeared in about ten minutes, carrying two bags at her side. I got out of the car and went over to help her get loaded up.

“Are you ready?” I asked.

“What?” she shouted.

“Are you ready to go?” I asked again.

“I can’t hear you. Oh. I forgot my hearing aids,” she said loudly. “I’ll be right back.”

And with that she set off at a snail’s pace for the still-open garage door. I watched as the hall light turned on. Then the bedroom light. After a few fumbling minutes, the bedroom light switched back off. Then the hall light winked out. Finally, the garage door began to close. She limped her way to the car, side to side, side to side.

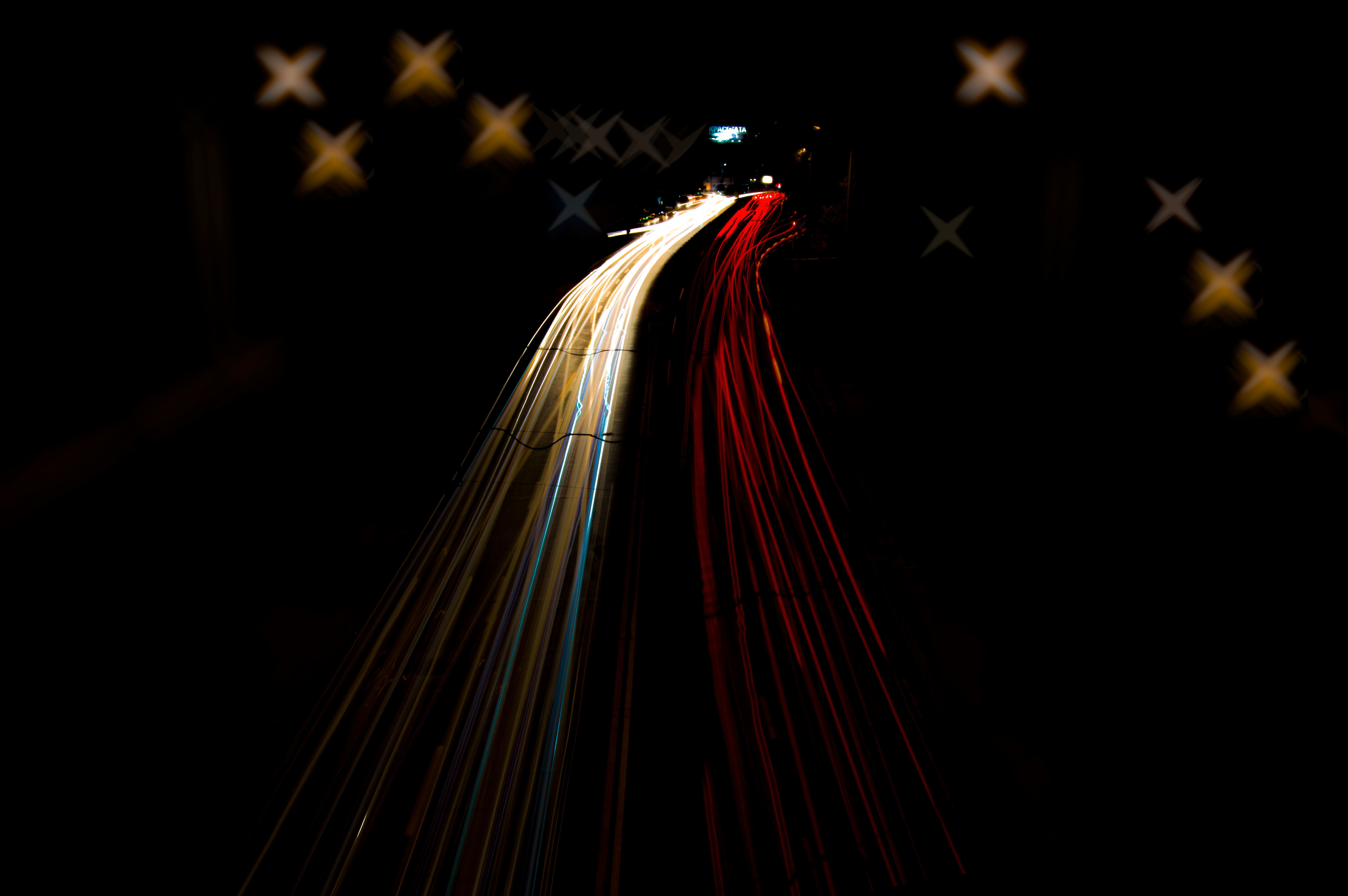

I confirmed her address, and we started out. It was cold and dark, and she did not live in the city so the roads were vacant.

“The other drivers have always waited,” she said, perturbed.

“Oh,” I said in a kind voice. “I see. I’m sorry.”

“Now I’m here in my old clothes because I didn’t have time to change.”

I nodded. She sighed.

“It’s very difficult getting over to see my husband,” she continued. “The taxis always take so long. And they’re very confusing about how to pay. How do I pay you?”

“It’s all on the app, ma’am. You don’t have to do anything.”

“Tip?”

“Tips aren’t expected,” I said. “You don’t have to worry about it.”

She sat there in silence for a moment, but then, as if she was scared she might lose my attention, she jumped back in again.

“It’s difficult getting over to see my husband. Very difficult. I don’t drive anymore. My son is so busy. I try to get over a few times a week.”

She sounded like she was trying to convince me that she was doing her best.

“I’m sure you do your best,” I said. We kept driving.

“Do you know where you’re going?” she asked. “Sometimes they don’t know where they’re going.”

I showed her the app’s GPS on my phone. When we got to the senior living center, she directed me through the maze of side roads and parking lots. I pulled up outside a small, single-story cottage. It was bright and it looked warm.

“That’s it,” she said, sounding relieved. “He still has his tree up. I don’t know why he still has his tree up.”

She got out of the car and I helped her with her bags.

“Do I have to pay you?” she asked again.

“No, ma’am, it’s all taken care of. Are you okay from here?” I asked her.

“Thank you,” she said, and suddenly her voice was apologetic. “Thank you for listening to an old lady. You know, I really miss him.”

“I’m sure you do, ma’am,” I said.

There was gentleness in her voice, the first I’d seen or heard from her all night. She turned away and went to the front door. It was unlocked. She disappeared into the bright lights of the house. I stood there for a moment. I got into my car. I drove back into the cold, dark night.