I sat on a small stool in between two hospital beds. There were maybe twelve beds in the boys’ hospital ward, which was actually a sturdy, huge, permanent tent. The tent was in the middle of an open-air trauma hospital surrounded by 12-foot-high cement blast walls topped with razor wire. Beyond that? More layers of blast walls and fences and trenches, the makings of a high security prison, only this place was trying to keep people out, not in. Just beyond the fence were the suburbs outside of east Mosul. The air was cool, with a slight breeze, and the sky was slate gray.

Later, I spoke with one of the directors of the hospital, set up and installed by Samaritan’s Purse at the beginning of 2017. She said that a few weeks before we arrived, there had been a suicide car bomb along with a few other incidents in Mosul, all in the same night. Dozens of casualties had arrived at the hospital, so many that the entire staff, even those supposed to be sleeping, were called in. Still, there were not enough people, so non-medical staff were called in to help. Their job?

To sit with the dying.

She said she sat there in the midst of all those beds, each bed holding a person who could not be saved, and she sang and she prayed and she waited while each and every person took their last breath.

This is what some people on this planet are doing. While I worry about where my next paycheck will come from or complain about the temperature of my latte, there are people in northern Iraq, accomplished, talented, dedicated people who could have high-paying corporate jobs but instead choose to go to the ends of the Earth and sit with strangers while they die.

This is the ministry of presence. This is what I learned about during our trip to northern Iraq.

* * * * *

I’ll be honest: I felt very out of place there in the hospital. The doctors and nurses scurried here and there, from tent to tent, all with such purpose. We tried to stay out of the way. There were three, state-of-the-art operating rooms, a women and children’s area, an entire section where the staff lived and ate (no one left the hospital unless it was to travel back to Erbil), and a men’s section completely cordoned off with its own blast walls – any male between the ages of 15 and 50 who came to the hospital without ID was placed in that section until they could be positively ID’d as anyone other than ISIS.

And there I sat. Quiet. Not speaking the same language as the children I hoped to comfort. Feeling very inadequate. Learning about the ministry of presence.

Beside me, the boy began to moan. He pulled the blanket up over his head, arched his back, and let out a long, low groaning that seemed to emanate from his soul and have no end. I looked around urgently – why wasn’t someone helping him? He seemed to be in a lot of pain. An older man came over to the bed and scolded him, shushed him. I looked over at the nurse.

“He’s autistic,” she explained. “That’s the boy’s uncle. His father is in the men’s ward until he can be ID’d.”

One of the girls who worked in the hospital grabbed Murray’s guitar and sat down beside the autistic boy. She started strumming chords, three or four different ones, creating a simple, steady melody. The other boys in the room, most of whom had broken arms or bandaged fingers, clapped their hands together gingerly and smiled. The boy beside me, the boy who had been moaning, peeked out from under the blanket. His dark eyes unblinking. His mouth closed and silent. She kept playing. He watched her fingers.

Then he started to sing.

His voice was mystical, magical, in the way Arabic singing is. It was like the sound of a different era. It was like his voice was coming to us from a thousand years ago, through narrow city streets and over boulder-covered mountains. And, remarkably, his singing was in perfect pitch, perfect rhythm. Our friend kept strumming, and he kept singing, the words wavering out to us like an apology, or the offer of friendship.

Someone asked the interpreter what he was singing. She smiled a sad smile.

“He is singing a lullaby to his mother,” she said softly. “His mother who is now dead.”

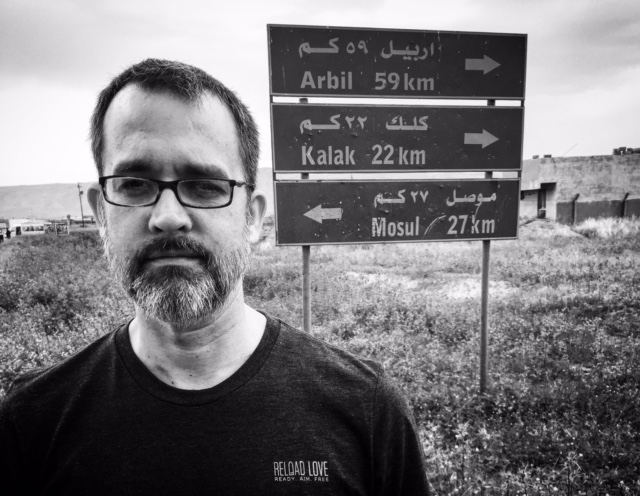

I traveled to Northern Iraq with a group called Reload Love. They take spent bullet casings, melt them down, and turn them into jewelry to raise awareness and money to support children impacted by terror. They send aid to in-country partners that have expertise in rescuing children from harm’s way and provide much needed assistance, including relief supplies, children’s programs, and safe spaces such as playgrounds. Reload Love is doing incredible work. You can find out more about them, as well as check out their beautiful line of jewelry, here.

The ministry of presence. Where there’s still music to be heard. Hauntingly beautiful Shawn.

I was so moved by this post. My son is 14 and on the autism spectrum. The thought of him suffering in this way is eased only by the hope that if he were in this situation, someone like you would be sitting there, offering that ministry of presence. Praying for this precious boy, so beloved in the sight of God. Thank you for sharing your experiences in these Iraq posts.

Beautiful! I have worked with autistic children and they love music ,I believe it touches them in a special way they respond immediately I love the term ministry of presence ,

This is such a sad, beautiful post. When you said, “this is what some people on this planet are doing”. It hurt my heart, because so many times I complain about such trivial things. My car isn’t warm, it’s too windy, the water took to long to get hot in the shower. There is nothing in my life even half as bad as what some of these children must be enduring. I heard you On the Catholic Channel a few days ago and had wanted to read the blog. Thank you for bringing attention to thee children. I hope more people take a moment to reflect on their lives and give back. God Bless