Death refuses to negotiate, that old son of a gun. It is a silent wanderer, coming and going as it pleases, and when it comes, there is no use bartering with it.

Still, we can’t help ourselves. We make an offer. We try to change its already-made-up mind.

* * * * *

I remember when he came into our lives. Dean was, and always has been, one of these people who is fiercely alive. He was at first the slightly older boyfriend of my cousin Andrea, but he never seemed older—he seemed like a kid. They married and he jumped into our extended family feet first, rivaling all of us when it came to athletic ability, courage, and competitive spirit (the last of which is saying something).

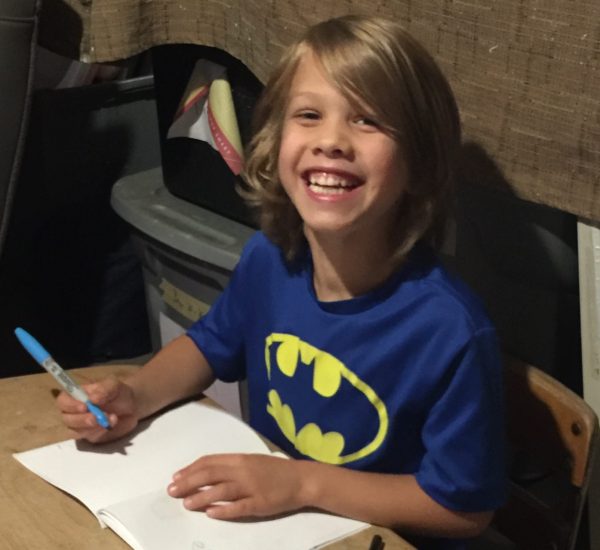

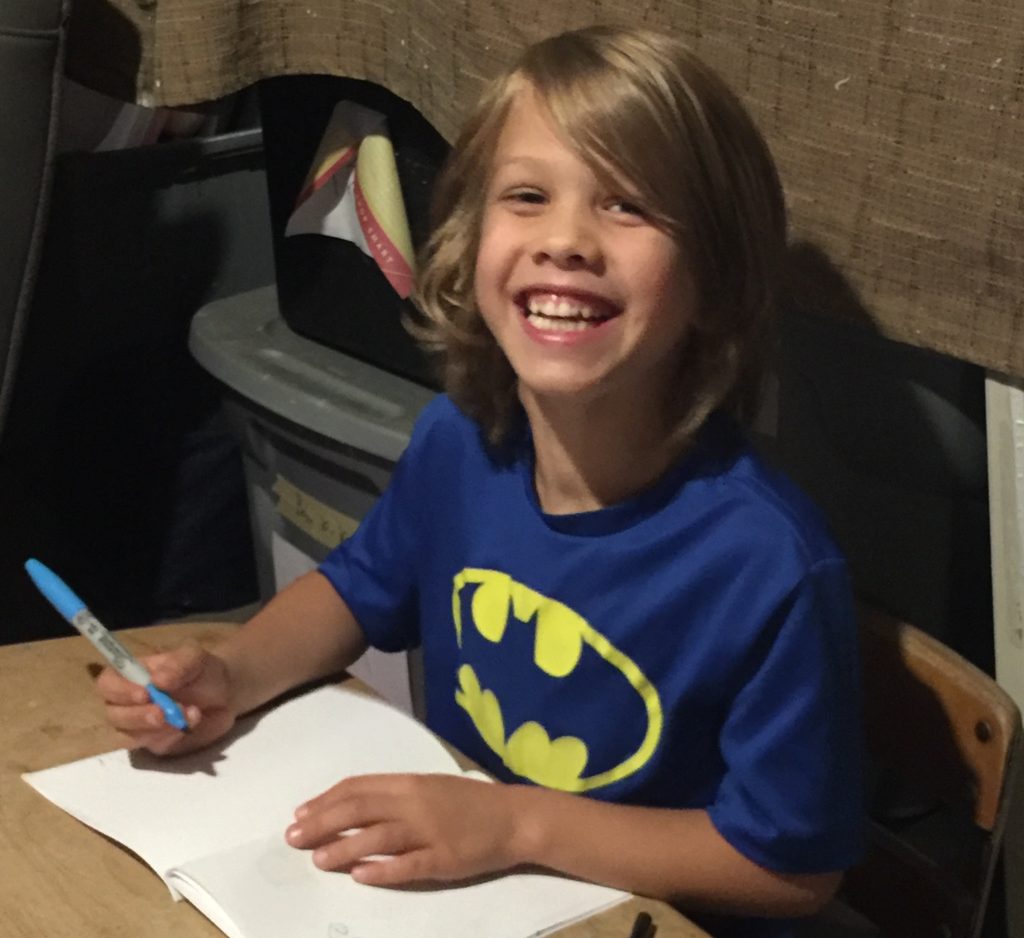

But there has always been something ineffably soft about Dean as well, so that when he talked trash over some outdoor game you knew that, at his core, kindness was somehow tangled up with his words. This softness became tangible when he had, first, his three girls, and then, tagging well on behind, his son, who I once saw him looking at with amazement, as if wondering, How could this remarkable thing have happened to me in my later years? When his youngest daughter battled cancer, I watched his eyes fill with love and sadness and slowly grow older, and when she came through it, he was still Dean, and Andrea was still Andrea, but they were something else, too, something more ordinary and more remarkable.

At a family gathering 18 months ago, I was talking with one of my cousins about the way my theology has changed in these recent years, how much of what I believe is crumbling or changing, and Dean, sitting at the other end of the table, heard us. He slid over to our end, leaned in, and listened. He asked a question here or there, but mostly he listened, his face intent and curious.

Dean died from Covid-19 this week. One of the last photos Andrea shared was of her and her kids looking up at the outside of the hospital from the sidewalk. The glass was reflective, so that they could not see Dean waving to them from his room. But he could see them.

Dean and Andrea and the girls live in Virginia and we did not see them enough. I tremble to think of the gap he leaves in his family’s life. And still we try to barter with death, as humans always do, have always done, perhaps, since the first death. I think of the last line of one of my favorite books, A Prayer for Owen Meany:

“O God — please give him back! I shall keep asking You.”

* * * * *

Earlier in the day we had learned that my Great Aunt Naomi had passed on, cancer being the vehicle. She was a writer; in another life, perhaps in a different culture (she grew up Amish) and under different circumstances, she would have been a famous author. Words meant a great deal to her, so that she didn’t waste them, or toss them here and there like too many of us do. She journaled as if her life depended on it; at times, perhaps it did. She lived with a kind of fierce courage, a deep foundation of grit and hard work and determination, someone from a different era completely.

When she saw me, it was always with eyes lighting up in a smile. She called me “Shawnee” and asked what I was writing. Once, she signed up for one of my writing classes and came to all eight weeks. She was around 70 years old at the time, and when she read her writing, we all listened, breathlessly.

* * * * *

And so in this Valley of the Shadow, we go about our ordinary lives that suddenly feel quite remarkable. Lucy makes an apple pie and Maile teaches her the intricacies of a flaky crust and we tell stories of the other great pie makers in the family, matriarchs who have gone on to that far green country. We play cards and the noise of the kids that normally scrambles my brain feels somehow like a balm. Leo has a tired tantrum and says through tears and a broken heart, “But I WANT to be annoying!” I wish Cade wasn’t at work.

It is the ordinary that becomes extraordinary in this valley. It is lying next to Maile in bed and holding her hand while reading Jim Harrison’s Legends of the Fall; hearing Lucy singing a Ray Lamontagne song in her bedroom for no one but herself; hearing the three chimes distant in the house as Cade gets home from work after nearly everyone else in the house has fallen asleep.

It is the crooning of Patti Griffin:

Where is now my father’s family

That was here so long ago?

Sitting round the kitchen fireside

Brightened by the ruddy glow

We shall all be reunited

In that land beyond the skies

Where there’ll be no separation

No more marching, no more sighs.

That song could be sung by my children now, in these latter days. I am the father now, and it is my family that’s leaving, my family who used to sit around the kitchen together, my extended family who we long to be reunited with.

* * * * *

I escape the light and warmth of home, take Winnie on a walk through the dark city. We stand in the open green together and take in the steeple that rises over the Lutheran church, and the Bethlehem star that still splits the skyline over Lancaster General Hospital. We walk the late-night sidewalks, and though it is only 9:30 p.m., we do not pass another soul.

And, after a time and an age, we come home through the alley. Winnie flinches at the gate. She always does. There is something about it that spooks her, so that I have to coax her through that narrow space of darkness. And I realize this is what we all must do—walk each other up to the gate of death, some of us balking more than others, some of us passing willingly, and help each other through.

Sometimes there is scratching and clawing and struggling, even a bit of panic, but eventually I calm her, and we pass.

Only one thing is certain—no matter how we barter with death, we will all have a turn to pass through that gate. But it’s not something to be afraid of.

Home is on the other side.

* * * * *

I woke up this morning, and I thought it was all a bad dream.