The table is set, and the late-winter night settles on the city. The candles dance, smooth in their movements. The air smells of baked Brie and the wine is uncorked.

There is a knock, and kind faces peer through the glass. I go to the front door, open it, and friends spill in along with the cold. Hugs and smiles and laughter. I’ll take your coat. What can I get you to drink? What have you been reading? Our conversations quickly veer towards books and words and the things that have moved us.

We sit at the table long into the night, our glasses empty. Must nights like this end?

* * * * *

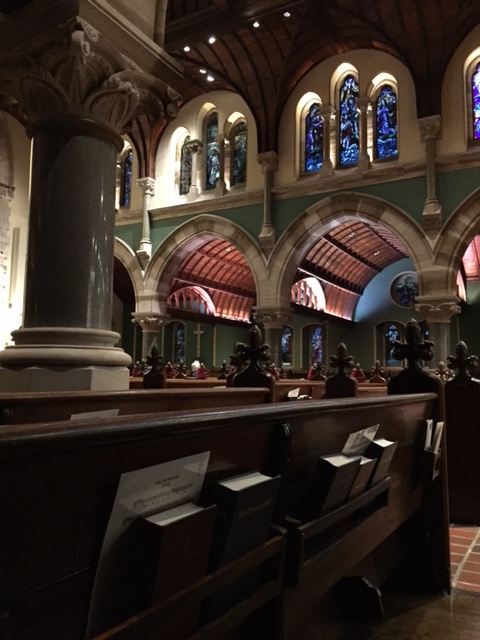

I wander the cold streets of Nashville, fresh from the Ash Wednesday service at an Episcopal church. The night is freezing cold, and the wind whips its way around corners, through alleys, up against buildings. I pull up the hood of my winter coat, my eyes watering. I turn a corner and walk downhill, slip into a hotel, and make my way to the bar.

There, friends. There, a warm drink. There, we wonder about the nature of things, the presence and absence of God, the strange ways we were all brought up to think about things. We move from the bar to a table. I take them in.

* * * * *

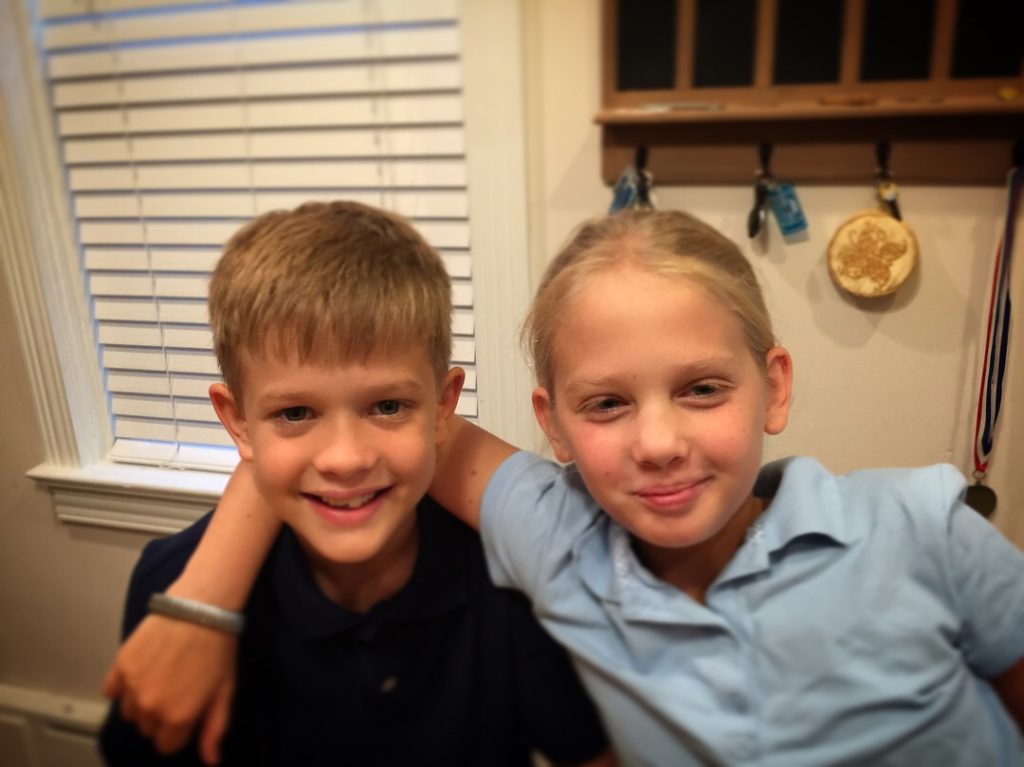

I have spent meaningful time with well over twenty wonderful writers in the last two months. Maile and I met up with some friends in Kentucky for a long weekend. Not long after that, I traveled to Tennessee and caught up with a few more friends there. The following weekend, we invited friends over for dinner–writers and small publishing house owners and a couple of my favorite booksellers. These times with creative people were meaningful, saturated with a desire for hope and beauty to find their way to the forefront of our culture.

As I think back on the last few weeks, I am made aware of the fact that each of the writers I’ve talked to and hung out with recently have two things in common.

First of all, every single one of them writes beautifully. Their stories are stunning, their nonfiction work moving. They are very good at what they do, accomplished, and dedicated to the craft.

Second, few of us are able to make a living strictly from these artistic endeavors. Most of us do other things to help pay the bills.

Doesn’t this beg a question? Or two? Or three?

Such as, what does it look like to be successful as a creative person?

Such as, what are my goals?

Such as, why write?

* * * * *

Instead of following those questions too far down their respective rabbit trails, today I’m thinking of all you writers out there, toiling away in obscurity. Writing your hearts out. Revising. Looking for agents and publishers. Independently publishing and marketing your work.

This is good work that we do.

Making money while doing something does not inherently prove or disprove its worth.

Not making money while doing something does not inherently prove a thing to be with or without value.

Why write? Here’s how some authors have answered that question:

“Any writer worth his salt writes to please himself…It’s a self-exploratory operation that is endless. An exorcism of not necessarily his demon, but of his divine discontent.” – Harper Lee

“Writing eases my suffering . . . writing is my way of reaffirming my own existence.” – Gao Xingjian

“I believe there is hope for us all, even amid the suffering – and maybe even inside the suffering. And that’s why I write fiction, probably. It’s my attempt to keep that fragile strand of radical hope, to build a fire in the darkness.” – John Green

“I just knew there were stories I wanted to tell.” – Octavia E. Butler

* * * * *

There is a table that is set for you, writer, no matter why you write, no matter how much money you make, no matter the size of your audience. And all you must do to be welcome at the table, to join in with the banter and the conversation and the laughter and the sadness of all the writers in the world, and all the writers who have ever been, is to pick up your pen, or open your laptop, and write.

Simply write.

In our most recent podcast episode, I make a confession, Maile talks about depression and writing, and we explore the ways and means of revising. You can listen HERE.

If you’re interested in receiving an ARC of my upcoming novel, These Nameless Things, find out how to win a copy HERE.