I’m sitting at the small red table beside one of our large living room windows, looking out at James Street. There’s our porch, the wide sidewalk, the busy street. There is the sycamore tree, ancient and leaning, the leaves gently browning in this mid-autumn light. It is 50 degrees and the sun is shining, shining, shining, as if summer is still within its grasp.

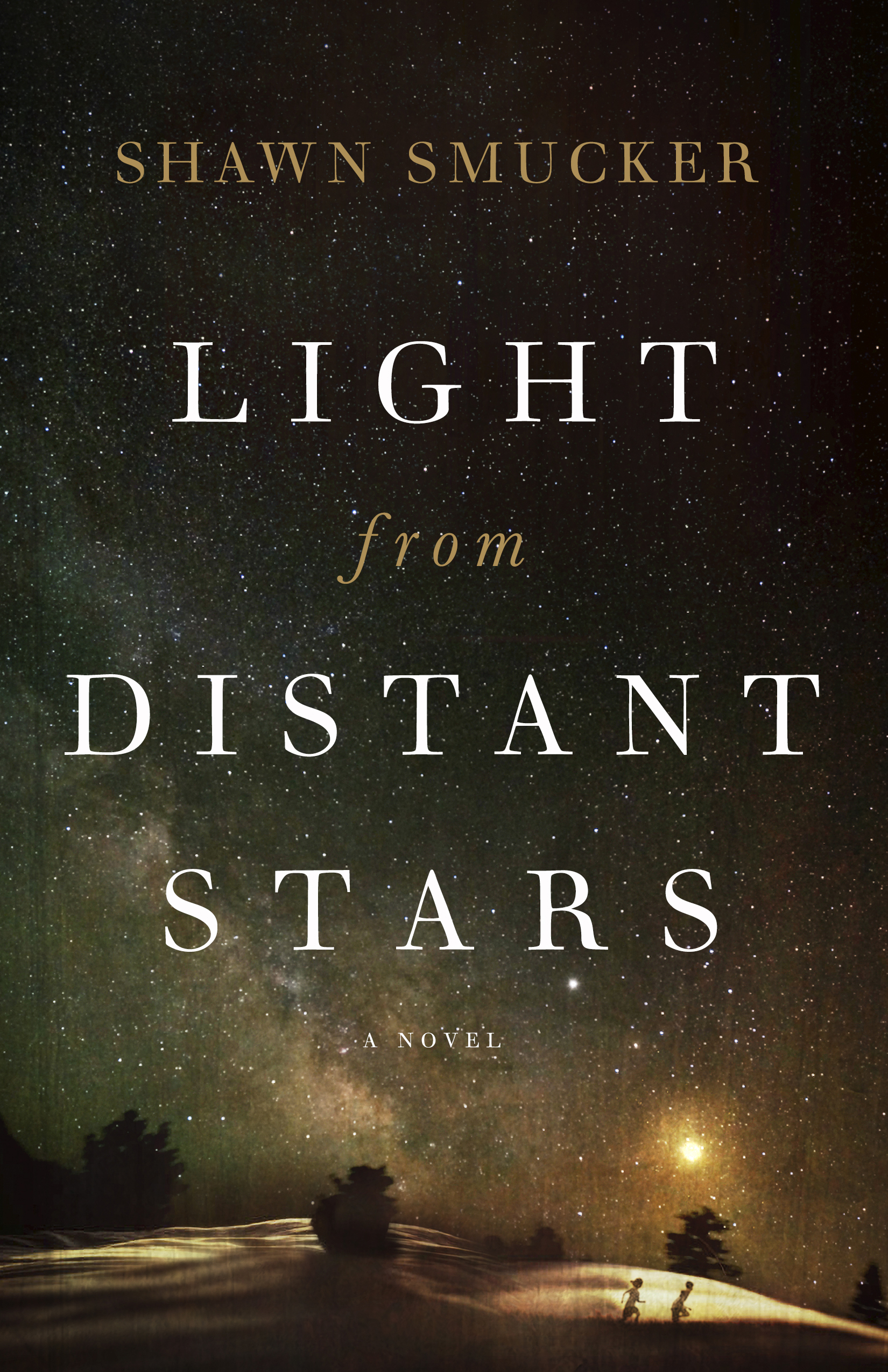

My book, Once We Were Strangers, released only last week, but I am in the thick of editing my next novel, one that releases in July of 2019. I can tell you now that it’s called Light from Distant Stars, and it’s the most challenging story I’ve ever tried to write. It is a standalone novel for grownups, not connected with my YA novel The Day the Angels Fell. But I have lots of time to tell you more about that.

What I want to tell you today, or share with you I guess, is the fact that even in the writing of this current book, in working through the edits, I am assailed by voices of self-doubt and questions about my ability to write well. There has been no magic turning point, at least not for me, where I have woken up self-confident and swaggering, convinced that I am finally the writer I have always wanted to be. Not when I co-wrote my first book and saw it in Barnes and Noble in 2008. Not when I signed a contract with my first agent, or landed a book contract, or when The Day the Angels Fell won an award.

And yet. There has been something magical about the last few weeks, a kind of turning point. I have experienced a peace in who I am, in what I write, in the words that I share – no matter the sales numbers, no matter the Amazon rank, no matter the mentions or shares or high-profile praise (or lack thereof). I am determined to enjoy each of my writing days, to work hard at getting better, to read more widely, and to sink deep, deep, deep into the stories I am creating. God is there, somewhere, waiting for me.

I know now that there is no Promised Land in the distance where, once there, I will have arrived – this creative life is nothing but a journey, nothing but one more word, one more sentence, one more chapter, and one more story.

This is what I offer you today, in whatever creative pursuits you are digging into: give yourself the freedom to chase excellence, to go after whatever creative thing is calling your name. Don’t be afraid, and when you are, let it fill you with exhilaration at the risks you are taking. Keep going. Keep moving. Keep breathing. Be present, really present, wherever you are.

This isn’t just for writing – it’s for painting and photography and starting a business and running for office. It’s for when you become a parent or get married or take a trip or start a church. Keep going. Keep moving. Keep breathing.

Anyway, these are my thoughts today, looking out the window onto James Street, watching the traffic go by, pondering a sycamore tree that was probably planted when my great-great-grandfather was a boy – the same man who used to write on the walls of his barn, stories and news and thoughts about life. That is all I am really doing here. That is all any of us are doing.

And here is the cover of my next novel, in case you were interested.