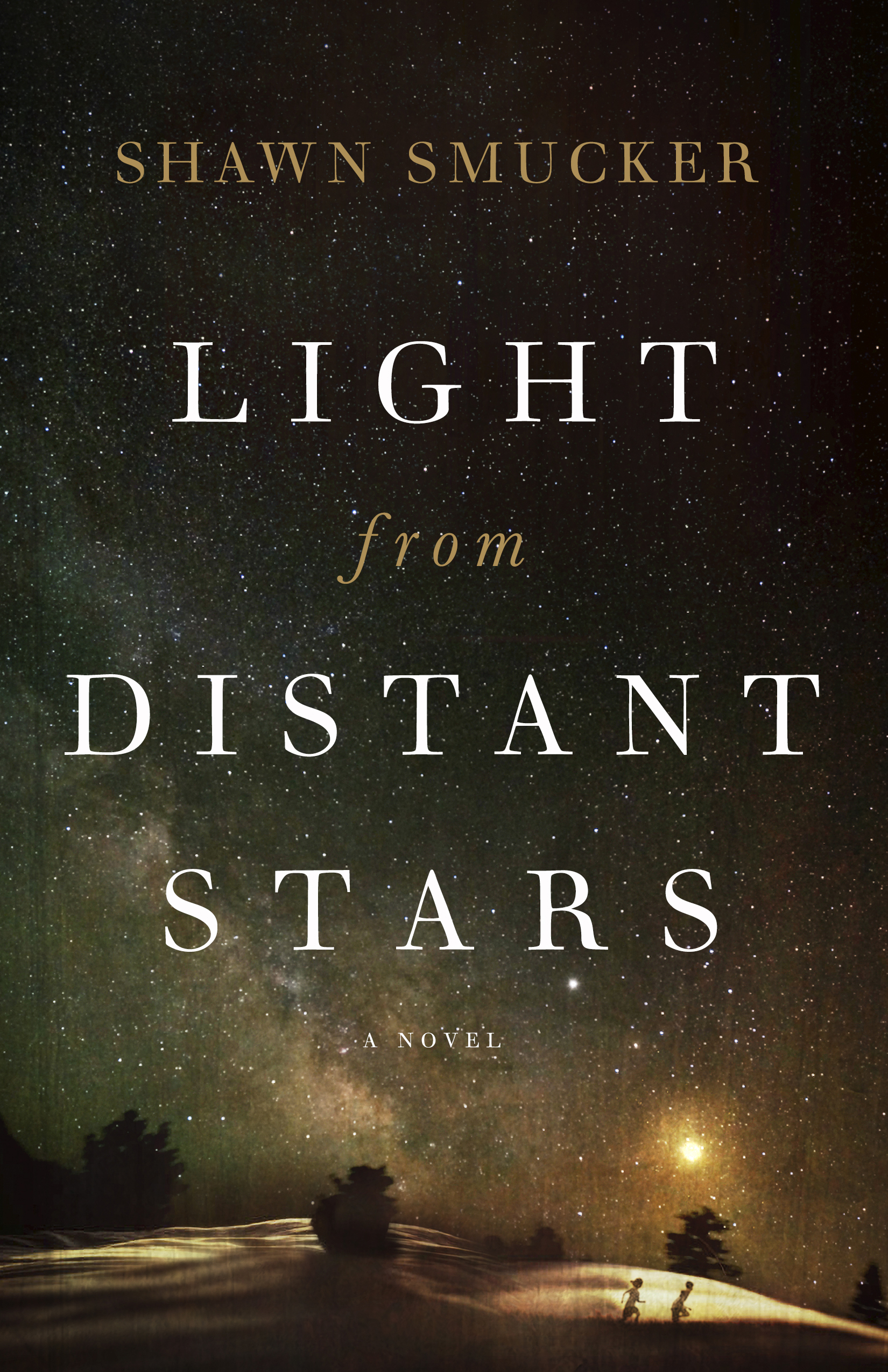

The book I wrote with my friend Mohammad, about his family’s journey to the US from Syria as refugees and then the journey of our friendship, has released! It’s called Once We Were Strangers. You can check it out HERE.

“Mohammad,” I said. “I’m sorry I missed your call.” It was Sunday afternoon, and we were driving home from church. The kids were chattering or arguing or quoting Jumanji 2 for the millionth time. The radio was too loud. I turned it off.

“Shawn!” he said, in that voice he always uses to answer his phone, that voice that makes it sound like he has been waiting a million years for me to call him. “I tried to call you. How are you?”

“We’re good,” I said. “We’re good. Is everything okay?” I had noticed he had tried to call me twice in a row, something he has not done before. He grew silent for a moment, and he didn’t seem to know how to proceed.

“My mother called from Syria. My father died.”

“Oh, Mohammad. I’m so sorry.” I knew his father had been ill for a long time, but when we last spoke of him, he had been doing better.

“Yes,” he said, his voice suddenly hoarse. “Yes. Can you come to my house today? I am having friends over, since my father died.”

“Of course. What time?”

“1:00. 1:30?”

“I’ll be there.”

* * * * *

I pulled onto his street where he lives in the southwest section of our city. Normally, the sidewalk in front of his house is not lined with cars, but on Sunday at 1:30 I had to drive further along to find a parking space. I got out, walked towards his house, and saw a group of seven or eight Middle Eastern men standing in his small front yard, smoking. I walked up, and they introduced themselves in broken English, then went on chatting to each other in Arabic. As more men arrived, they made their way around the circle, greeting each person. Some of the men kissed each other on each cheek.

“Where are these men from?” I asked Mohammad as they chatted.

“Dara’a, Dara’a, Damascus, Aleppo,” he said, pointing, making his way around the circle. They smiled kindly at me. They laughed to each other, joking quietly. Soon there were fifteen or twenty men there. Mohammad’s brother-in-law, a young man around 20 years old, came outside with a pot of coffee and a tiny cup, smaller than a shot glass. He moved around the circle, one man at a time, pouring a mouthful of strong, black coffee, and offering that tiny glass. Each man drank the scalding coffee like a shot. He came to me, smiling. We had met before. I took the tiny mug and drank it down.

* * * * *

Soon the men filed in, still chatting somberly in Arabic. We came to the doorway, and everyone took their shoes off on the stoop. Muslim men are particularly talented at this–it may not sound like much, but taking off your shoes so that they do not touch the inside of the house and so that your feet do not touch the outside sidewalk takes some forethought. You have to arrange your shoes so they will slip off, step inside with your stockinged foot, shake off the second shoe outside, and go in. I remembered doing this in Istanbul, when we went into a mosque.

There, we sat quietly on the sofas and chairs, waiting. Mohammad’s boys, who had been strangely absent, appeared with two purple plastic covers, spread one in the living room and one in the dining room, on the floor. These were the tables. They came in again making many trips, bringing all the food, the drinks, and the plates for everyone. When everything was ready, we moved cross-legged to the floor.

I waited, watched, tried to avoid making any foolish missteps. The man to my left gestured for me to fill my plate, so I took a scoop of rice and a few round things that looked like potatoes but were actually fried meal filled with meat. I didn’t want to take too much food. The man to my left smiled at me, abruptly took my plate and added two more huge scoops of rice, a few more of the potato thingies, and a massive piece of meat still on the bone. The plastic plate now bent to nearly breaking. He handed it back to me with an Arabic sentence that seemed to be something along the lines of, “There. That’s better.”

The men began eating, and I followed hesitantly behind, watching them. Someone said something in Arabic, and a few of the men chuckled. But an older man, sitting at the opposite side of our table, smiled kindly at me and said, “No, no, he’s just watching us. He doesn’t know how to eat like we do, so he is watching. This is good.”

* * * * *

After the meal, we washed our hands and got back up into our chairs. They spoke quietly in Arabic. I could not understand a single word, but it struck me that there is something of the lament in the sound of Arabic, the way it strikes the ear, the way it curls through the air. It is a language that sounds sad to me. Maybe it’s just because of that particular setting, but it seemed to serve them well, and I could have gone on listening to the sound of it for a long time.

I started talking to the man beside me. He has been in the US for 20 years. When he took his citizen’s test, it was just after 9/11.

“The woman asked me if I wanted to change my name,” he said with a smile. He shrugged. “I didn’t mind. I thought it might be a good idea. There was so much anti-Muslim sentiment in those days. My given name is Abdul-Haran. I went by Haran. She asked me what I wanted my name to be. I didn’t know. She asked me if I liked Bob, or Johnny, or Jim. I said, ‘How about John?’ So, that’s my name.”

I marveled at the easy way he talked about exchanging his name for a new one. I looked around the circle at these men, all of them refugees. None of them grew up wanting to leave their homes. Most of them left friends and family behind. Yet there they were in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, working hard, making a living, raising families.

“I think I’ll call you Haran,” I said, smiling. He laughed.

* * * * *

We sat for an hour after the meal, and besides my conversation with Haran and a few tidbits from Mohammad, not an English word was spoken. It was one of the most poignant cultural experiences of my life. I looked over at Mohammad’s boys–they can speak Arabic, but they cannot write it. They never learned it. I imagine that their own children, one more generation removed, might not see the value in learning Arabic.

* * * * *

One of the men got up to leave. He stood at the door and held out his hands, palms up, and chanted out a prayer in Arabic. The men stopped in the middle of their conversations, some closing their eyes, some also holding out their hands. Then he smiled and walked out. This happened a few more times. I asked Mohammad what the men said.

“They are saying prayers for my father,” he said, staring at the carpet in front of him, his dark eyes seeing things from long ago, far away.

In the corner, two of the men work prayer beads through their fingers, one bead after the other, one after the other, for the entire hour.

* * * * *

Finally, it was time to leave. Everyone decided to do this at once, without discussing it. I stood and put on my coat. One of the men came over to where Mohammad and I stood. He said a long prayer with Mohammad, and Mohammad seemed close to tears. The man had a very kind voice, deep brown eyes, and was the only man there with a beard. Then, the man turned to me. Mohammad introduced us.

“This is our imam from the local Islamic center,” he said. The man looked at me and shook my hand with both of his. He had a gentleness about him that was disarming.

“I’m Shawn,” I said.

“Thank you very much for being here,” he said, and there was such a depth to his thanks. “Thank you very much for coming.”

He turned and walked out. I followed the men into the cool day. The sun was shining.

The book I wrote about my friendship with Mohammad is now available, Once We Were Strangers. You can check it out HERE.