For the last four days I hung out with an unlikely friend.

His skin is the same rich color as the Mexican earth from which his ancestors eked a living. His hair is so black it soaks up the light – all except the thin, crescent-shaped scar, subtle as the small stream that runs past my house, hidden in the undergrowth. On his face is etched the pride of a Native American chief, the kindness of a paisano, the mental quickness of some desert fox.

Twenty-two years ago, on a small airstrip in South America, a Panamanian soldier shot him in the head. The unexpected gunfire raked his entire group, and one of the AK47 rounds deflected up off the tarmac and removed a handful of his skull. When he came to, his scalp burning, one of his teammates knelt beside him, asked him a question.

“What should I do with this?” his teammate asked him. He couldn’t move. He glanced to the right, straining his eyes. The teammate held a large portion of his brain’s right hemisphere in the palm of his hand.

* * * * *

When I picked him up at the airport, he smiled, a nervous invasion of emotion. He wore a black hat, perched backward on his head. I helped him into the car, unsure as to exactly how much aid he required. I knew he had tunnel vision. I knew the left side of his body had virtually no feeling. Still, he smiled.

“I got it,” he said kindly, and I knew he meant the door.

* * * * *

It’s amazing that he walks at all. It’s amazing that he can talk. Twenty-five years ago he was what is referred to as a “physical specimen”: barrel-chested, walking on thighs as thick as many people’s waists. Now he owns a small limp, and a left arm that will float up into space if he doesn’t hold it down.

Sometimes, when he stays by himself in a hotel, he has to ask a stranger in the lobby to do the right hand button on his long-sleeved shirt – his left hand just can’t do it. Sometimes, if he forgets to ask someone at night to unbutton it, he is forced to sleep with his shirt clinging to his right wrist.

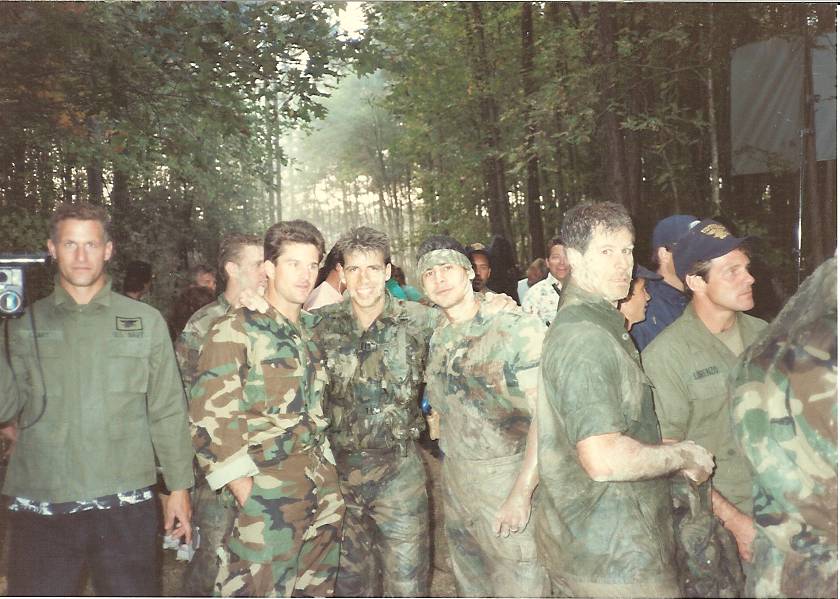

When I first introduce him to people, they’re intrigued. He is, after all, a very kind man. When I tell them he was a Navy SEAL, their response changes.

“Wow,” most people say, their eyes opening wide, reaching to shake his hand. But I can tell he doesn’t like being introduced that way, so I stop telling people. And I get used to their casual indifference, their glances at watches. Not because of him, but because of them. Because this is how we are. This is how we treat people, when we don’t know their story.

* * * * *

My unlikely friend went through triage and ended up in the expectant area. In other words, the dead pile. Lucid, he lay there watching people walk by, yet he was unable to move, powerless to get their attention.

He lost his family, his nearly perfect body, and much of his ability to think. It has taken him twenty-two years to regain the mental skills required to hold a normal conversation.

And for his pain, he receives a modest disability payment each month from the US Government. This is not meant to be a political statement. He doesn’t care about the money.

But I know he cares about the way people treat him.

We should be nicer to strangers. We have no idea the sacrifices that they have made.

“This is how we treat people, when we don’t know their story.”

That line haunts me. And I suppose that’s why I’m so interested in everyone’s story and the aspect of social work I enjoyed the most. Because we never know why people are the way they are from a 5 minute conversation but if we take a little time, we might learn a piece of who they are. Lord help me if I ever overlook someone like your friend.

I think that I need to begin to treat everyone that crosses my path as if they had sacrificed as much as he has.

Not that it’s possible. But I think it would be worth the effort.

Humbling…

Thanks for reading, Mike.

It is truly unbelievable how much knowing a person’s story changes how you interact with them.

On a much lighter note, I was totally judging the new pastor and his wife at my church for being super so-cal people. Turns out they were from a little town in Northern california and actually had a hard time living in SoCal. Woops. My bad.

Your story is way better than mine.

I guess we need to search out stories. And share ours.

Beautiful story and well written.

I hope you write about him again, I want to know more about him.

Thanks Janet. His story is one of the books I’m currently working on, but as we progress with the book I’ll definitely be sharing more here on the blog.

Well told. I especially like the tensions between your descriptions of him and how he perceives himself. It’s not just a story about judging others, but how we consider who we are: honor mixed with humility.

Thanks for the poignant message. I have the highest respect for personnel who have served and sacrificed for our country. Please thank your friend for his service.