I was in junior high when we boarded the yellow school bus and pulled out of the parking lot. We were quieter than usual, I remember that, mostly because we were all a little nervous regarding our opponents that afternoon.

McCaskey High School.

I grew up in the country, first on a farm and later in a house situated on a one-acre plot surrounded by fields. On humid summer nights, I would go for runs on those back country roads, completely at home in that feeling of incredible aloneness, winding my way through corn that grew well up over my head. That dirt, that quiet, that empty sky got into my blood.

I say all of that only to explain how uncomfortable I felt as the bus pulled into the city, made its way in among the row homes and the cracked sidewalks. When we passed the prison, I stared up at its castle-like turrets, its barbed wire and high brick walls. When we got off the bus and walked into the city school where the game was being held, I had never felt more out of place.

I have to be honest and say that I’m sure much of my nervousness came from entering into a space dominated by people of color. My high school had only a handful of young people who were not white. I was comfortable there in my back country school, tucked in among so many that looked like me, sounded like me, believed like me. Going into that city school when I was a kid, I was afraid of those kids because they didn’t look like me.

* * * * *

When Maile and I realized she had reached the end of the line when it came to homeschooling, that she could no longer teach our four oldest kids and remain sane, our immediate thought was, “We have to move.” After all, through various life circumstances, we found ourselves living in the very city I had feared as a child. Except we loved it.

But send our kids to those city schools?

I don’t think so.

So, in the winter of what would be our last year homeschooling, we put our home on the market. Our dear friend and realtor Dave, who has so loyally trekked alongside us through our many moments of indecision, listed the house for us.

One problem, though. We didn’t want to leave the city. We loved it on James Street–loved our neighbors, loved the convenience, loved all the things going on, loved the diversity our kids were growing up around.

But the schools.

Two families helped us right the ship. We invited the Kings over to our house, a family who had made the homeschool-to-city-school transition, and we talked with them long into the night. They told us stories about their kids finding their way in the School District of Lancaster (SDOL), a Title I school (read: full of kids growing up in poverty). And their stories heartened us.

Then, not long after that, my sister and brother-in-law came over with their family, and we spent the evening talking about the city. At one point, Ben asked us, “So, why are you guys moving?” Maile and I looked at each other.

We didn’t know the answer.

* * * * *

“We’ll just take small steps,” we told each other. “We don’t have to make any final decisions yet.”

And the first step was sending our oldest son to McCaskey High School with a friend he could shadow for the day. He came home totally amped up. He loved it. He loved the school, the vibe, the adventure of it all.

We had not expected that.

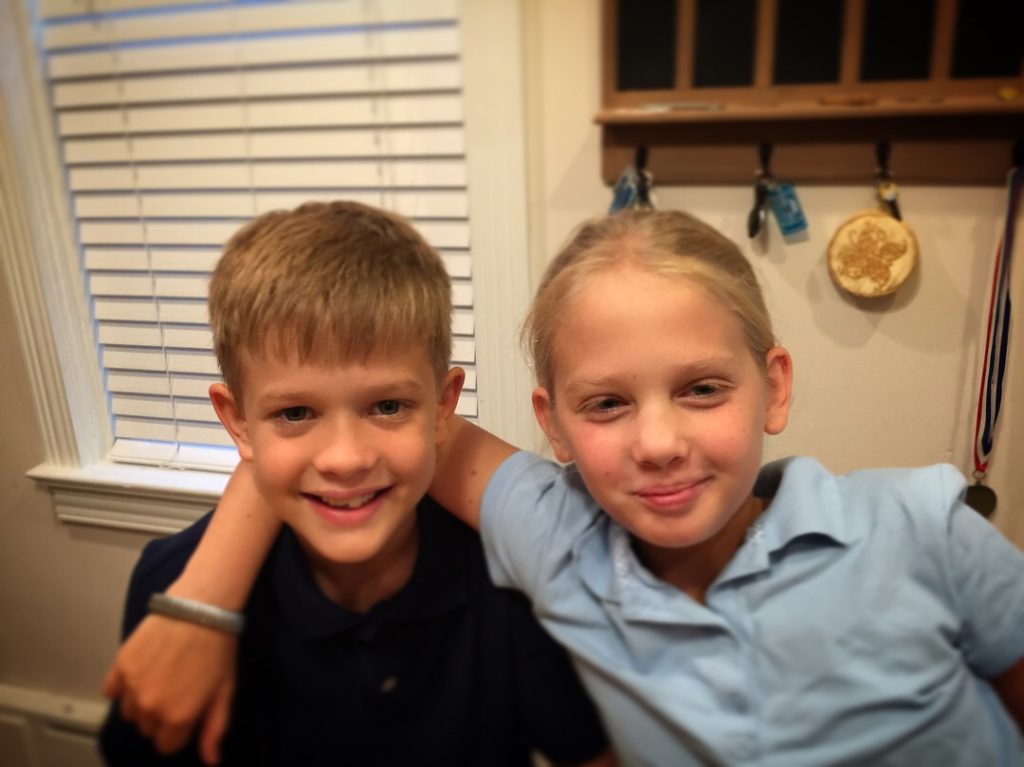

The second step was to visit the elementary school where our two middle-aged kids would go. We walked the halls of Ross Elementary with them, led by the most wonderful principal, and I found myself totally shocked. This was not the city elementary school I had expected. I don’t even know exactly what I had expected. But the principal knew every child by name. The kids were quiet and respectful. There was art on the walls and we could hear sounds from the music room floating down the hallways.

It reminded me of the elementary school I had attended as a kid. The one out in the country.

I remember walking home with Maile, two of our kids running ahead of us. I watched them navigate the traffic lights, chatting the entire way. They had loved it. Maile looked at me.

“Why are we moving?” she asked.

* * * * *

We called Dave, our realtor. We asked him to take our house off the market. Poor Dave. We’re always doing this to him. The next day he called, as if with one final test. “Are you sure you don’t want to move? I’ve got an offer right at your asking price.

We were sure. We weren’t going to move.

* * * * *

A few weeks ago, I went to school with Lucy on Saturday morning for Tag Day. It’s the one Saturday of the year when several hundred McCaskey students involved in choirs or bands take to the streets and ask the people in our city if they’ll donate money to the music program. Just the thought of going door to door made me nearly sick–I hate that kind of thing. I think Lucy felt the same way.

At school, we loaded up our 15-passenger van with high school music kids and drove to our assigned route. They hopped out, and I couldn’t believe how enthusiastic they were. We went from house to house, but instead of getting the response I expected (basically, “Get off my lawn!”), we were greeted by person after person who loved Lancaster city, loved McCaskey, and couldn’t wait to give some money. We even passed people on the sidewalk who wondered what we were doing (the kids were dressed in choir robes and band outfits), and many of those people pulled out their wallets on the spot.

The kids even sang at some of the houses where we stopped.

Our small group of 12 kids raised over $500 in a few hours.

* * * * *

There’s something to be said about not making decisions out of fear. If there’s a direction you think you want to go but you’re afraid, take the next small step. You’ll find your way.

If you haven’t had a chance to listen to the first episode of the podcast Maile and I recorded about creativity, publishing, and the writing life, you can check that out HERE. Episode 2 comes out tomorrow!