Most mornings, when I’m going to drive, I peel myself off the floor where I’ve been sleeping beside Leo’s bed. He’s not been sleeping well at night. I creep out of the room, make some delicious Passenger Coffee (Union blend), throw on some clothes, and climb into my cold car. At 5am, the city is quiet and crisp, a new dollar bill. The street lights are sharp, like stars.

I pull up to a produce warehouse and wait for my fare. He comes out: an African-American kid, maybe 20, hood pulled up, hands deep in his pockets. He gets into the front seat.

“Morning,” I say, confirming his destination. “You work through the night?”

He nods and shivers, and his voice is kind.

“Morning, man,” he says. “I’m tired. And I’m freezing.”

I wonder if his work place is refrigerated, seeing that he works with produce.

“I’ve got heated seats,” I say, chuckling, reaching forward and pushing the button to turn on the heat in his seat. “But it’ll probably put you to sleep.”

“I can sleep anywhere.”

He grins from under his hood and I can feel the connection between us. He’s tired and cold, like me. He’s working hard, for himself or someone else. Third shift, man. Third shift sucks.

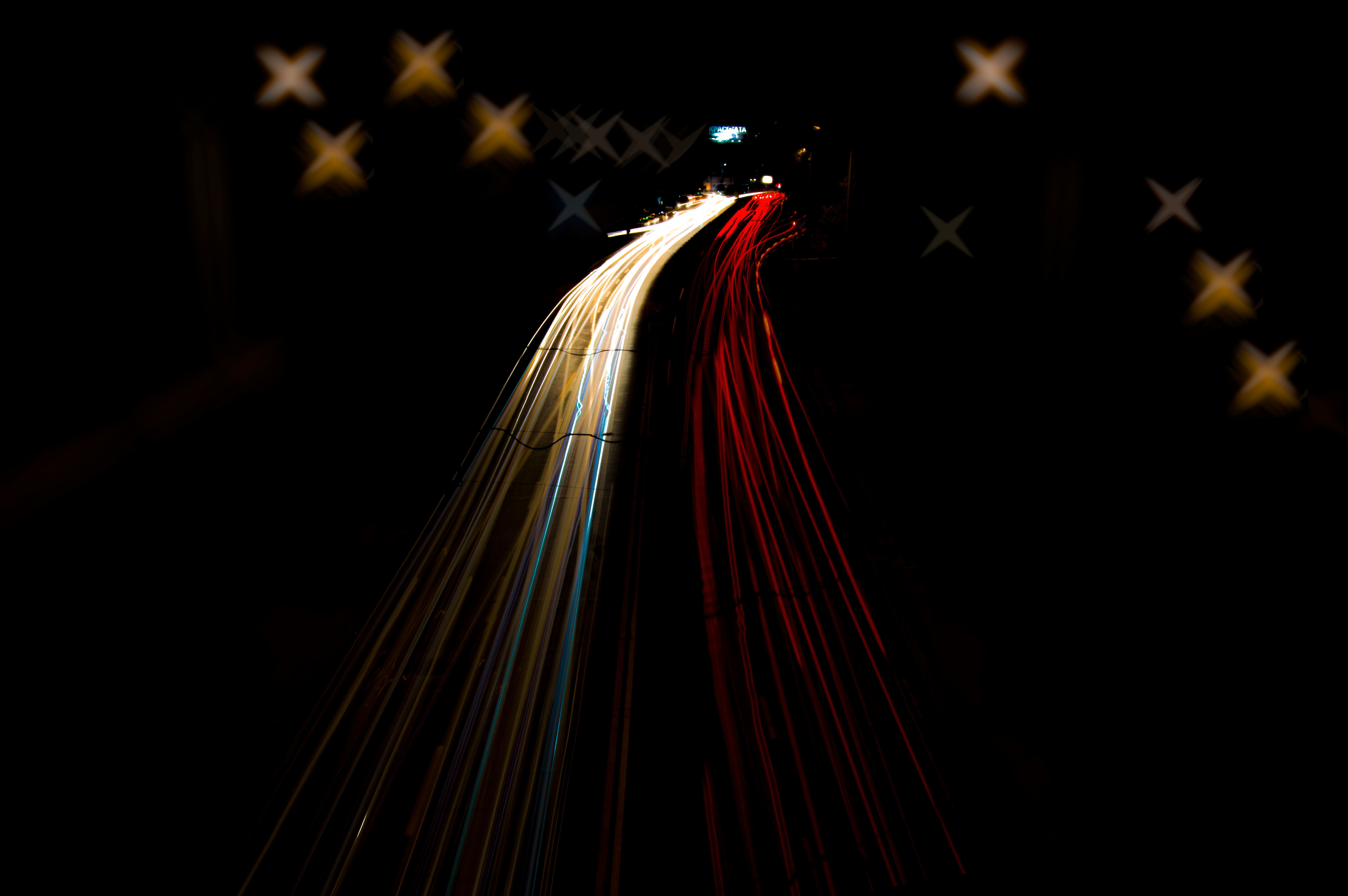

His destination is fifteen minutes away. After three minutes, he’s asleep, and there I am, driving this kid home from work. His breathing is heavy, his mouth wide open, like one of my kids, and as the sun rises behind us, over the highway, I feel an almost desperate tenderness towards him, the same kind of feeling I feel when I wake up in the middle of the night to take one of my own kids back to bed.

We get to his apartment building, and I can see the river. The sun rises over it. He startles awake, rubs his face.

“Sorry, man,” he says, shaking his head. “Wow, I was out. Right here’s good.”

I pull over, wish him well, and he gets out. And I go on with my day.