I drive the truck faster, weaving past cars on the city streets. I nearly pull out in front of someone and hit my brakes. We are 35 minutes from the birth center, and Maile’s labor has started. I stop at a red light just as another contraction builds inside her.

This is our sixth child. I know in an intimate way the process my wife’s body goes through when the baby has decided to come. For example: Maile hums through her contractions. It’s quiet at first, barely a breath, but as the contractions get stronger and closer together her voice swells into a loud kind of almost-singing. It’s a prehistoric chant, something in her DNA. But as we sit at the red light, and the contraction swells, that particular pressure transforms her humming into a guttural grunt. I also know what that means.

“Do you have to push?” I ask, looking over at her. This is not a good time to push. We are too far away.

Her lips are pursed and white around the edges. She’s still exhaling the remnants of the last contraction. She nods.

“I wanted to that time.”

The traffic is slow. We hit every light red. Another contraction comes in, tides back out. Another. All those people we pass in their cars, living their normal evenings. Going out to eat. Going home from work. Talking with friends on their phones. Can’t they see there is a miracle in our truck, barely waiting to break forth?

“Play that song again,” Maile whispers. The song is “Born” by Over the Rhine.

I was born to laugh

I learned to laugh though my tears

I was born to love

I’m gonna learn to love without fear

“You should probably drive faster,” she says in a flat, calm voice, but there is a trace of urgency, like a small, red thread on a white carpet.

Pour me a glass of wine

Talk deep into the night

Who knows what we’ll find

I look both ways and pull hesitantly through the red light, then drive the rest of the highway in the center lane, my four-ways flashing. We are 20 minutes from the birth center. But we are finally out of the city. We are fleeing into the country shadows, the sun setting behind us.

* * * * *

This I’ve also seen: when Maile begins labor, when the contractions start to come closer together, she withdraws inside of herself. There is a labyrinth she follows to the deepest parts, and when she’s there, when she’s in active labor, I can’t find her anymore. She wouldn’t recognize me if we passed in the street.

Intuition, deja-vu

The Holy Ghost haunting you

Whatever you got

I don’t mind

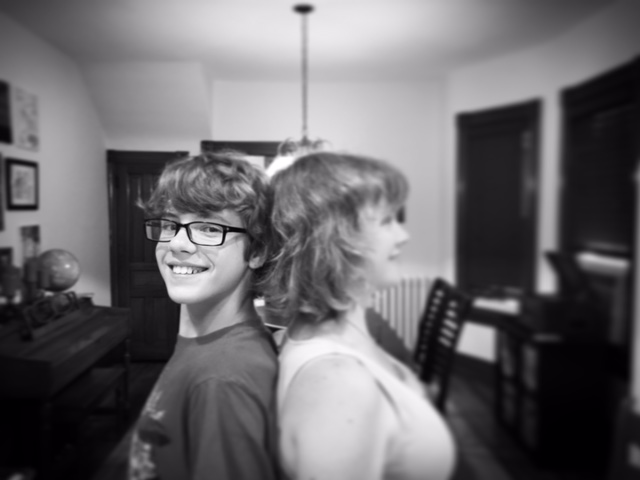

At 7:30pm on Saturday night, one hour before we raced down the turn lane of Route 30, she said she wanted to go for a walk, so she and I set out along with Leo and Cade. We went west on James and turned north on Prince and as we walked down the long hill, the sun was setting off to our left, its light dripping into a vacant parking lot. A cool breeze swept by with the traffic. The air felt lighter somehow, as if August had persuaded October to come and take over the evening duties.

We turned east onto Frederick Street. Cade walked ahead. Leo said hello to a little girl playing on the sidewalk. Maile slowed down. She breathed deep, and I could see it beginning to happen: the withdrawal, the searching. She was looking for a way into the labyrinth.

We turned east onto Frederick Street. Cade walked ahead. Leo said hello to a little girl playing on the sidewalk. Maile slowed down. She breathed deep, and I could see it beginning to happen: the withdrawal, the searching. She was looking for a way into the labyrinth.

“You okay?” I asked her. There was some fear in her eyes.

“That was a strong one,” she said, walking with one hand supporting her back. “I’m scared. You’re going to have to help me with this baby.”

I nodded quietly.

“You got it, babe,” I said. “One at a time.”

We walked all the way to Duke, turned south, then doubled back on Prince towards home. A homeless man pointed at her stomach.

“I saw another one of you over on Lime,” he said, practically shouting. Indescribable joy was etched on his face. We smiled and nodded.

“Over on Lime!” he insisted. “Pregnant ladies everywhere.” Then he turned and walked away.

We got to the last crosswalk. Soon we would be home. The sign was orange, don’t walk. Maile bent over then arched her back, breathed deep again, hummed. That was the first hum I’d heard. The contractions were serious. She stood up, looked like she might throw up. Her eyes were far away. She was entering the labyrinth.

“Maybe we should head into the birth center,” I said, not expecting her to take me up on the suggestion. She doesn’t like to go in until it’s time. But she surprised me, there on the corner of Queen and James, just opposite the Greek restaurant we love. She didn’t even make eye contact with me. Only nodded.

“That’s a good idea. We should probably hurry a little bit.”

I wondered what it would be like to deliver a baby in the Suburban. I turned to Cade.

“Hey, buddy,” I said. “Why don’t you run ahead and tell Mimi we need to go? Now. Tell her we need to get moving, fast.”

Cade stared at his phone.

“Hey, you,” I said, half laughing. “Get moving.”

“Dad,” he said, looking slightly embarrassed. “I’ve got an awesome Pokemon on the line.”

“What?” I exclaimed. He paused, swiped his fingers up and down his phone, then took off in a sprint.

“I got him!” he shouted joyfully over his shoulder. Maile and I shook our heads. We both laughed.

Put your elbows on the table

I’ll listen long as I am able

There’s nowhere I’d rather be

That’s when we drove out of the city. That’s when I weaved in and out of city traffic. That’s when Maile started to feel an urge to push.

* * * * *

We slip away from the setting sun, now 15 minutes from the birth center. With every contraction I ask her if she needs to push. Sometimes she says yes, sometimes no.

These are the hills where I grew up, the sprawling, green fields with July corn as tall as a man. These are the summer nights I cut my teeth on. This is the land inside me, the place I will someday go home to when my life is over, my far, green country. I am not afraid of helping my wife deliver a baby in the truck, if I have to – not with those fields as witnesses. It almost seems fitting, that a child of mine would spring into being in the midst of the corn and the tobacco, the trees and the fireflies, the quiet, curving roads and the distant storm clouds.

But we make it. There will be no Suburban birth. We pull into the birth center and the nurse lets us in after hours and we go into the same room where Leo was born. The same room. The same bed, the same tub. I remember when Leo was born. I remember texting everyone the news, including our friend Alise who had recently had a stillborn son. I wanted her to know we were thinking of her. There is such joy and sorrow as I get older. Joy inextricably mixed with sorrow. They’re a tangled mess.

The contractions come closer together now, and Maile is far away. She is lost in the labyrinth, trying to find her way to the elusive center. She hums through contractions. She strips down and climbs into the warm bath, facing the corner, squatting down as far as she can, her arms out in front of her. In yoga, it is close to the child’s pose.

She whispers prayers into the water when the pain becomes unbearable. Her breath scatters shallow ripples over the thin surface. Or maybe it is the Spirit. She wants me to push deep into her back, and I press with the heels of my hands. I feel her spine and the deep muscles of her lower back, her ribs.

Bone from my bone. Flesh from my flesh.

She presses herself down until I think she might melt into the water or split in two. She wants help out of the tub, so we move her to the bed. She hums through the contractions and the humming turns louder and louder, rises up over itself until she sounds like a muezzin calling us all to prayer. Her powerful voice gives me chills. She moans and cries out and pushes.

Secret fears, the supernatural

Thank God for this new laughter

Thank God the joke’s on me

We’ve seen the landfill rainbow

We’ve seen the junkyard of love

Baby it’s no place for you and me

The way a child comes into being from a woman is the birth of a galaxy. It is searing pain and numbing joy; it will break you into interstellar pieces. A bundle of powder-coated limbs slips and jumbles its way into the world, still attached to the source. A squirming heap of carbon and water covered in blood and a ghostly vernix. Believe in miracles. They are born every day, attached to their mothers.

When Maile realizes the baby is a girl, she raises her face towards the ceiling. Her smile is like those clear shafts of light that break through storm clouds.

I was born to laugh

I was born to laugh

I learned to laugh through my tears

I was born to love

I’m gonna learn to love without fear

“What a gift,” she kept whispering over and over again. “What a gift.”

Later, in the quiet, the labyrinth far behind (or perhaps all around, with us finally residing in the perfect center), we name her Poppy Lynne Louella.

Poppy for the ruby red fields in England we often hiked through, gazed at.

Lynne for my Aunt Linda who died a month ago, who rose through a bright pink sunset and fireworks that split the sky.

Louella for Maile’s grandmother, homeless and alone at a young age with only her sister, married at age 16, one of the strongest women we ever knew.

Poppy Lynne Louella.

What a gift.

Italicized lines are from the song “Born” by Over the Rhine, my favorite band. You can purchase the album, “Drunkard’s Prayer,” or listen to more of their songs, HERE.