I must confess

I painted the green table

and the yellow chairs,

the ones

we bought when we were first married

fifteen years ago

when my stomach was flat

and we didn’t shy from starting movies

(and other things) after 11.

When sleep was commonplace, like mis-

matched socks,

and silence was everywhere in the house

so thick you could trip on it

or get lost in it.

Of course,

you asked me to paint the table

and the chairs

but I didn’t

think it would take so many coats to cover

all the gashes

and scars

left by a thousand Scrabble games

hot pans of Rice Crispy Treats

four years in storage while we lived

in England

unsecured trips in moving vans

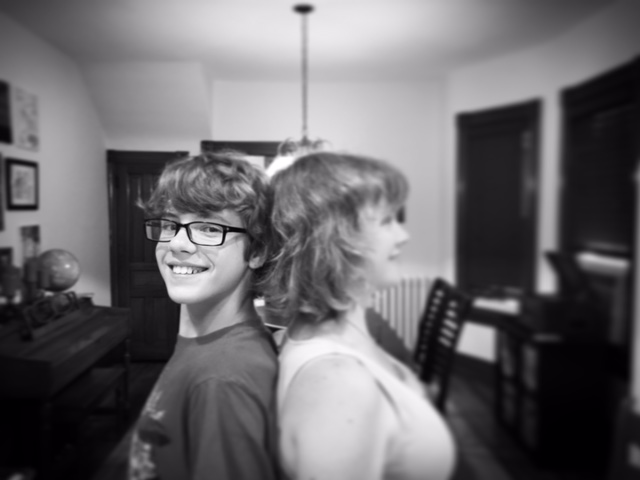

then teething children gnawing and racing

their matchbox cars past bowls

of cereal that left little pale rings

like the wispy ones that circle planets.

And then there were the permanent markers

that bleed through sheets

of multi-colored paper

or the demanding bang of miniature

forks and spoons chipping away.

But the new red paint will never cover

over the way we sat on those chairs,

elbows on the table,

and cried

after two miscarriages. Or the lost

friends. Or the pain

and joy

of moving on

to new places.

There are some things paint cannot cover.

Like conversations unfolding from

“Now

what do we do?”

or

“How could you say that?”

or

“I’m not doing well.

Not well at all.”

But also

“I’m pregnant,”

or

“I got the contract,”

or

“I couldn’t do this without you.”

Someone already scratched the table

despite my many warnings of the incredible

wrath that would fall from this

August sky

but when I saw in the middle of the new

scratch that the original dark green

was still there

under the red paint

all those years

just a thin skin away

I must confess.

I was relieved.

Because these years of ours

may look like a pock-marked tabletop

scarred and scraped,

but they can never be covered over.

And that is one thing in this world

that is exactly as it should be.

You can get my ebook of poems, We Might Never Die, for free HERE. Enjoy!